The point: Isaiah Armstrong's "work" had numerous serious code violations and did not follow relevant and accepted best practices. As a result, Isaiah Armstrong damaged my property.

Thickness of Slabs

According to Building Code 2009 of Alabama, section 1910.1:

The thickness of concrete floor slabs supported directly on the ground shall not be less than 3 1/2 inches (89 mm).

The code does not specify that patios are excluded and makes no allowances for the usage level of the slab, only that concrete floor slabs supported directly on the ground the must be a minimum of 3 ½ inches. Moreover, a reference to “driveways, walks, patios and other flatwork which will not be enclosed at a later date” is specifically called out in the Exceptions section of 1910.1 relating to the use of vapor barriers. This means that patios and other flatwork both fall under the remaining provisions of this code. One is a patio, the other is flatwork.

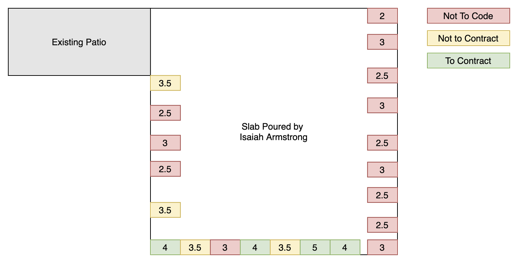

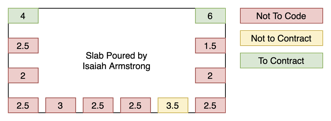

The slabs of concrete poured by Isaiah Armstrong varied between 1½ inches and 6 inches, but are not a consistent minimum 3½ inch height as specified in code. Of the 33 measurements I took around both slabs poured by Isaiah Armstrong, 22 of these measurements, account for a full 67% of both slabs, do not meet the building code minimum of 3½ inches.

Therefore, Isaiah Armstrong damaged my property by performing work not up to code.

Slopes and Drainage

According to the International Residential Code, Section R401.3 Drainage:

Impervious surfaces within 10 feet (3048 mm) of the building foundation shall be sloped not less than 2 percent away from the building.

While the overall slope of the slab is 4.45%, because the slab highly variable by following the slop of the land (see “Concrete Patio Not Built to Customer Specifications”) and is not consistently leveled, the slope of the first 1-2 feet in some spots are either zero or sloped slightly towards the house, before cresting at between 6 and 9 inches from the wall, and then falling at a much sharper and more pronounced angle. This will result in water entering the house at the weep holes as water runs along the valley created by this crest.

Moreover, as Isaiah Armstrong did not fulfill the part of the contract relating to handling the drainage (see “Gutter Downspout Drain Not Installed”), water from the downspout is going directly into this area and potentially behind the brick veneer via the first weep hole. And as I informed Isaiah Armstrong on June 16, 2021, a large amount of the roof drains to that specific downspout, greatly enhancing the possibility that this will happen.

If enough water enters it can cause water damage to the interior wall on the opposite side of the brick wall.

Summary of Code Violations

Code violations alone are enough reason that this work is completely and entirely unacceptable as delivered. It is a wholly unacceptable level of workmanship from someone who claims to be a trade professional. It is a core responsibility of a professional contractor to know about and adhere to the relevant building codes. Isaiah Armstrong either was not aware of or willfully ignored them.

However, beyond code violations, there were many, many other deficiencies with Isaiah Armstrong’s work.